Up ahead the road narrows and I need to scrub some speed. I roll off the throttle and reach for the clutch. My right foot should be nudging the shift lever on my old bike to select third gear, but my leg won’t move. Damn. And then I awake, not with a startled longing, but with a sense of resignation.

I am paralyzed from the chest down. Odd word, paralyzed is. It would seem to indicate rigidity. My lower body bends and moves, but I’m no longer in control. A decade has passed since the motorcycle accident, and dreams are the only place where I can walk or sometimes ride a motorcycle. My subconscious catches the mistake, however, and whispers, “you can’t be walking, you can’t be riding; you’re dreaming.”

I’m not a fabricator, I’m not a welder, and I’m not a mechanic. But I find solace in the intricacies of metal and gears—they’re a mental escape. Motorcycles have, for the most part, always had a role in my life. Now, instead of the ride I focus on the creation. I know paraplegics with trikes or outfitted sidecars, but it’s not for me. I’d rather spend hours in the shop, taking motorcycles apart, putting them back together, and hearing them run.

I’d rather spend hours in the shop, taking motorcycles apart, putting them back together, and hearing them run.

We knew we’d have to move after the accident. While I was in the hospital my partner sold our house, and bought another. It wasn’t set up as an accessible home, but it proved easy to make ready for my return. Notably, there’s a four-car garage, and two bays are set up as a shop. It’s a place where I can work around a central motorcycle lift.

After my return home from hospital John Whitby came over, surveyed the situation, and rolled my tired 1966 Honda Super Hawk onto the bench. He took it apart and spread pieces of Honda everywhere—and then he left. It forced me to work through the motorcycle, helping me understand what I was capable of doing.

Small stuff on the workbench isn’t a problem. I can lift and install wheels or even mount a wiring harness and get the connections made. Heavy, awkward pieces such as engines and forks require an extra hand.

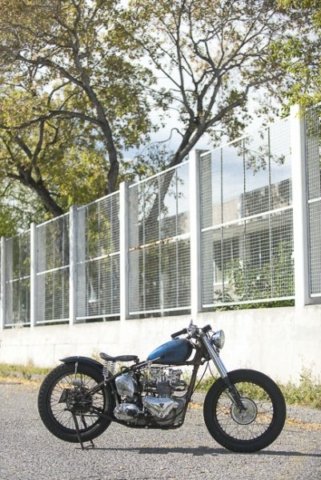

After the Super Hawk other projects have come and gone. But this 1951 Triumph T100 has been on the lift the longest. It started as the lower half of an engine. There was no head, frame or wheels. On eBay in Saskatchewan I found a 1947 Triumph rigid frame, fork and wheels. Rusty and crusty, the front of the frame had been brazed together at the neck—I found a replacement for it on eBay.

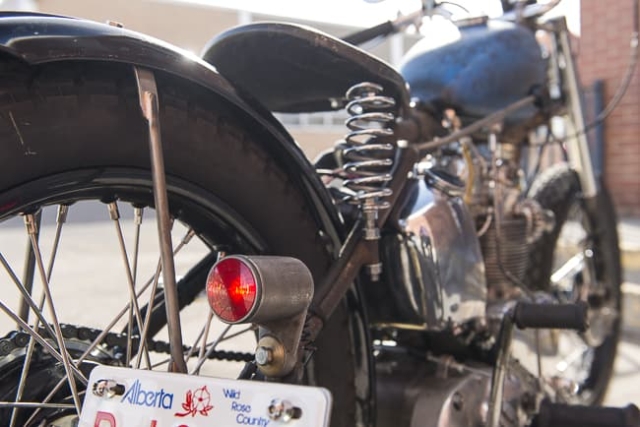

From the Saskatchewan wreck I used the rear frame section, fork triple clamps and front and rear hubs. Mike Partridge at Walridge Motors in Ontario sourced 19-inch front and rear rims and stainless steel spokes from Central Wheel Components in the U.K.

Calgary Powder Coating blacked out the rims, and Whitby assembled the wheels and mounted Dunlop K70 tires. New fork tubes and lower fork internals were put together from a number of sources—but mostly from bits found at the bottom of boxes stuffed in my garage.

Ebay provided the fuel tank and Jason Brunner of Airdrie helped fashion and weld the mounts, which are cut from pieces of exhaust tubing. Whitby bent a flat steel rear fender brace, but I cut that apart and connected the pieces with 3/8-inch round bar. The distressed leather seat is from Rich Phillips Seat Co. of Saint Louis, and I cut, shaped, and welded the mount.

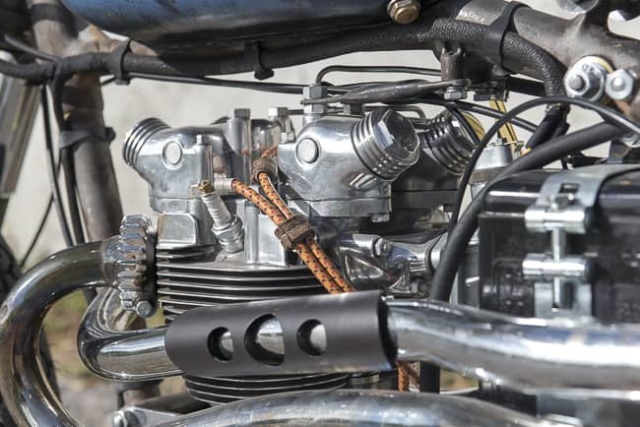

Triumph’s 500 cc all-aluminum T100 engine is simple, and my engine was disassembled and inspected. I think it had been rebuilt and never run, but the three-piece crank was taken apart, cleaned, and reassembled with new bolts. Babbitt rods were new and Whitby helped get the bottom end together. He also fitted the freshly honed cylinders—a job done by Mike Briggs at Performance Cycle in Calgary—over the pistons.

With the engine still on the bench, I installed a manual advance Lucas magneto. Geoff Abbott of Calgary machined an eBay-sourced cylinder head and found new valves and guides. I assembled the head with new valve springs before bolting it up and mounting a brand new Amal pre-Monobloc carburetor.

Alloy polishing was performed in-house (but not actually in the house) and there’s plenty of it. Cylinder and head fins were buffed, as were the rocker boxes, timing cover, and primary cover. Whitby found the outer timing cover in a local collector’s garbage can. The characteristic teardrop bulge was broken away, but metal craftsman Derek Pauletto of Trillion Industries made an utterly unnoticeable repair. Pauletto also welded in my handmade gas tank mounting bungs and oil tank top strap, and filled a small crack at the bottom of the neck.

I had two gearboxes, both presenting too many challenges to be successfully rebuilt. Wes White of Four Aces Cycle in California sent me one. It needed a new gear and both shifter fork rollers, but it went together nicely. I’ve always liked hand-shift motorcycles, and designed a rod and linkage that pivots in the sidecar mounting lug.

Wheel and engine fasteners were treated to a coat of cadmium at Victoria Plating in B.C., and two years after piecing things together I had a roller. I had issues with the clutch, which turned out to be a bad basket. But that wasn’t all. After assembling and adding oil to the fork, I discovered they were as immovable as the rear end, plus they weren’t oil-tight. Bob Klassen and I spent two evenings taking them apart and putting them back together. Movement was finally achieved, although being an early telescopic design travel is limited.

I’m OK with being in a wheelchair. It’s who I am now. When I’m in a room of 500 people, I might be the only one with a visible disability. But in that room there are others fighting their own demons—from addiction to familial dysfunction. And I don’t often get upset about being paraplegic—except when a motorcycle is nearing completion and it’s ready to run.

Whitby was the first to fire the twin, and it started on the third kick. Once the bike was run in and fettled, I had planned to take it apart and send the frame, fuel and oil tanks, and fender for paint. And then people told me they liked the organic look of a bare-metal bike. For now I’m keeping it as is, but I reserve the right to change my mind and paint it.

Last summer Klassen helped dial in the Amal before adding 130 miles to the Smiths odometer. He provided updates as the riding progressed. “The bike handles so nicely; fork action is good and both the front and rear wheels feel great,” he said. While he liked the hand shifter, he felt it was a shame to have to remove a hand from the handlebar to change gears—surely a case of form over function. Truthfully, the Triumph is a triumph of form over function; it will never receive much use—and none of it will come from me—but every time I roll out to the garage, seeing its form is more than enough reward.

Full gallery of Greg’s custom Triumph

Photos: Amee Reehal